Who gets to be a “founder,” and why? What are they founding? And for whom? What I emphasize in my research is that picking one origin story above all else often reveals more about the person doing the pointing than the event being pointed at. Early Americanists like myself love to talk about a vast diversity marking the past: Native Americans, Spanish, Dutch, French, Africans, English, and so many others. Stories must start somewhere, and the starting place is often critical to the story that unfolds.

#WHEN DID THE PILGRIMS COME TO AMERICA PROFESSIONAL#

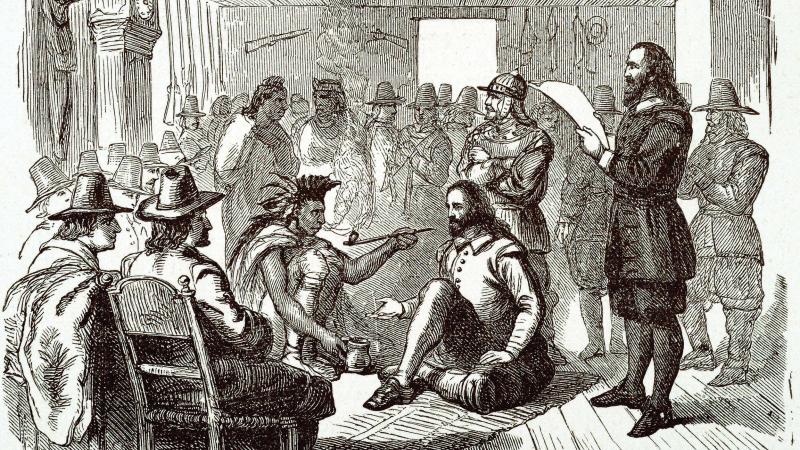

While the Pilgrims were not ‘first’ in any formal way, they were made first in order to define America as a certain set of ideals.Ĭontending for “founders” is often inherent to the doing of history-whether by professional historians or by the general public. During the Cold War, a concerted effort raised the status of this sermon into a foundational text of American history and culture-so that by the time Ronald Reagan started running for high office, he could make it the cornerstone of his campaign. In this 1630 sermon, Winthrop declared that “we shall be as a city upon a hill.” Though the sermon was never known, noted, or printed in its own day, these words by Winthrop were retooled to mark the origin story of a nation Winthrop never himself conceived. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the rise of an obscure sermon, A Model of Christian Charity, by the first Puritan governor of Massachusetts Bay, John Winthrop. And so, while the Pilgrims were not “first” in any formal way, they were made first in order to define America as a certain set of ideals. They could proclaim themselves a moral beacon to the world. They could claim to have established self-government. Through the Pilgrims, Americans could claim to stand for God, not gold for freedom, not slavery. So why do they make the list?Įver since the early 1800s, the Pilgrim origin story of Plymouth Rock has served to isolate a purer purpose for America, defining the nation as distinct from all other countries on earth. In many ways, they were late to the game. They were not the first people here, nor the first Europeans, nor the first Englishmen, nor the first permanent English settlers. What do all these different answers mean? They mean that America has many origins, and all of them matter. The Declaration of Independence and the American Revolution delimit “America” as a political nation, the United States, which began at a certain time. The arrival of enslaved Africans marks and defines America through the institution of slavery.

Beginning with Jamestown means identifying the first permanent English settlement. Starting with Columbus means locating an origin in the first Europeans. Starting with Native Americans means highlighting the first people to set foot in this land while also including all who have ever since come. But more than the messiness of a story with no solitary beginning, they also show how talk of origins does little to sort the truths of history and much more to identify definitions of “America” in the present day. They mean that America has many origins, and all of them matter. What do all these different answers mean? Intercultural and Interreligious Dialogue Topic Transatlantic Policy Network on Religion and Diplomacy.Towards a Global Culture of Safeguarding.Revitalizing Global Religious and Interfaith Networks.Politicization of Religion in Global Perspective.The Geopolitics of Religious Soft Power.

The Culture of Encounter and the Global Agenda.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)